Lifid

The death of a restaurant

About a year ago, in a somewhat Zen take on a declining situation, a local food aficionado wondered whether, if the Wild Boar restaurant closed, anyone would notice.

Well, did you?

Last week, the venerable home of haute cuisine with a cellar that wine writer Robert Parker would covet was essentially padlocked by representatives of federal bankruptcy court, ending its 16-year reign as the center of fine dining in Nashville.

Over the years, I had a number of opportunities to dine there. My experiences ranged from extraordinary meals to such insultingly poor treatment that I walked out before being seated. And now, as lawyers take inventory and prepare to auction off the wine and equipment, I have mixed feelings about the whole thing.

Restaurants are by nature fragile enterprises that deal in both culinary artistry and financial responsibility. It’s a sum of unique parts that includes a chef’s ability to realize plated dreams, a manager’s ability to maximize a diner’s experience, and a menu that puts people in the seats and profits on the books.

So what went so terribly wrong that Wild Boar slipped ignominiously from Chapters 11 to 7 to its last and final chapter?

Just as success is a balance, failure is a series of both bad decisions and unfortunate circumstances.

The Wild Boar’s descent began with the untimely death in 1996 of its owner and visionary, Tom Allen. It lost a passionate advocate who could bring people in through sheer charisma. His passing also coincided with downsizing in corporate dining. Gone were the big-ticket days when loyal customers wore out the numbers on their corporate credit cards, often night after night.

Still, Wild Boar held fast to its concept of continental cuisine, formal service and fine wine. Diners, however, learned that fine dining had evolved, and that the same quality of preparation could be found in more interesting dishes in more interesting, and casual, settings.

It wasn’t long before Wild Boar’s interior looked dated, if not downright cheesy, in its reliance on heraldic motifs. The food, too, felt more old-fashioned than classic, and over the last few years it sadly seemed irrelevant.

The service, too, devolved into being more haughty than haute, as if pomposity were the watchword to bolster past successes.

One evening I arrived with a reservation and was told to wait in the bar. I scanned the dining room and saw only one other table seated. The bar was empty, too, but we waited patiently for more than half an hour.

Finally, after expressing concern that we had to wait so long, we were told the maitre d’ would be with us shortly. After 10 more minutes, we walked out. While the restaurant had my phone number from my reservation, I never received a call, either of explanation or apology or an invitation to return. If you claim to be the best restaurant in the city, you call.

That, to me, signaled the beginning of the end, and I vowed not to return unless for professional reasons.

I did return; however, the circumstances were not what you would imagine. When chef Colin Quirk was lured away from the Ritz in Atlanta, it sparked a glimmer of hope.

He came highly credentialed and with quotes from other well-respected chefs. I wanted to let him settle in before a review, but I never had the chance. The restaurant filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy protection, and Quirk, seeing the blood in the drain, resigned his position.

So I returned during what ended up to be the seven-night reign of local chefs Kim Totzke and Laura Wilson, who against the advice of just about every restaurant professional in town decided to give it a whirl, knowing that it would probably last half a year at most, if that.

It’s remarkable what talented, passionate professionals can do in such a short time. They went from zero to menu in a day, bought a Big Daddy fryer at Wal-Mart (the Boar’s was broken) and turned out well-executed true bistro fare. As Totzke put it one day, „What do we have to lose?“

After the seared foie gras with green apple slivers in a reduction sauce proved a tremendous sweet-tart foil for the rich liver, I realized they lost nothing. After their tuna tartare timbale with its briny kick from a medley of Greek olives, they gained a fan. With 50 customers on their last night and more than 50 on the books for the night they closed, it seems I was not the only one who came for the chefs.

But it was too little served much too late.

When I spoke with manager and part-owner Brett Allen after the restaurant shut down, he said he felt relieved for it to be over, convincing me that the restaurant’s life support plug had long since been pulled. That makes it hard to mourn.

I don’t doubt that Nashville can support fine dining, but all the pieces need to be in place.

And now, as attorneys look through the bottles of Petrus, Cheval Blanc and the bottled glories of other chateaux, I am anxious to see what might fill this culinary void.

Source: tennessean.com

-

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun5 dagar síðan

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun5 dagar síðanÍsland tók yfir eldhúsið á VOX þegar Sævar Lárusson og Rúrik mættu til leiks

-

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel3 dagar síðan

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel3 dagar síðanSushi staðurinn Majó flytur starfsemi sína í Hof á Akureyri

-

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun2 dagar síðan

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun2 dagar síðanMeistarakokkar færa sælkeramat í hillur Krónunnar

-

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun5 dagar síðan

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun5 dagar síðanKristján Örn matreiðslumeistari bauð upp á glæsilegt jólahlaðborð á Gran Canaria – Myndir

-

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel4 dagar síðan

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel4 dagar síðanNýtt bakarí í undirbúningi á Öskjureitnum á Húsavík

-

Pistlar17 klukkustundir síðan

Pistlar17 klukkustundir síðanEinfaldlega íslenskt um jólin

-

Markaðurinn4 dagar síðan

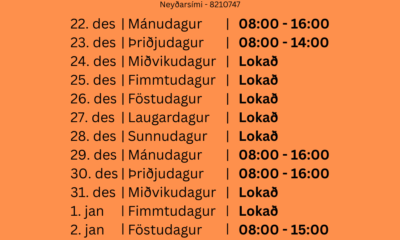

Markaðurinn4 dagar síðanRMK heildverslun: Opnunartími yfir hátíðarnar

-

Keppni3 dagar síðan

Keppni3 dagar síðanCoffee & Cocktails hreppti 1. sætið í Old Fashioned keppninni