Lifid

French Chefs Try To Turn Tables On Star System

PARIS, Feb. 23 — In the stratosphere of French gastronomy, the announcement was shocking: The world’s best-known dining guide was stripping France’s most famous restaurant — the Tour d’Argent — of one of its coveted two stars.

The 424-year-old establishment may have magical views of Notre Dame Cathedral, a wine selection of 800,000 bottles and ducks that arrive at the table with individually numbered certificates. But in the opinion of inspectors from the Michelin Red Guide, „the food has been declining,“ said Jean-Luc Naret, director of the annual reviews that can fill a restaurant or send it into oblivion.

The only response from Tour d’Argent, which was dropped from the top-level three-star rating in 1996, was a cryptic statement that expressed surprise and observed: „This decision coincides curiously with its wish to no longer appear in the Michelin guide.“ The book was experiencing unspecified „difficult circumstances,“ it said.

At an establishment where the cheapest dinner for two can top $500, that reaction had the ring of sour grapes. But in the last two years, some of France’s greatest celebrity chefs have revolted against the century-old rating system that has helped define haute cuisine for a nation that considers food and drink part of its patrimony.

They have tossed out the pretensions, dressed down their tables and lowered their prices for a generation they claim is fed up with stiff, stuffy, outrageously expensive dining experiences.

„There’s a feeling that the Michelin stars don’t fit what the new generation of restaurant-goers want,“ said Luc Dubanchet, editor of the restaurant newsletter Omnivore. „They don’t want condescension and decorum anymore. They want life and energy.“

„There’s a feeling that the Michelin stars don’t fit what the new generation of restaurant-goers want,“ said Luc Dubanchet, editor of the restaurant newsletter Omnivore. „They don’t want condescension and decorum anymore. They want life and energy.“

The Michelin guides use a system of up to three stars to rate top restaurants. One star designates a „very good restaurant;“ two stars means „excellent cooking, worth a detour,“ and three stars signals „exceptional cuisine, worth a special journey.“ The ratings are based on a long list of standards including quality of food, presentation and cleanliness of bathrooms.

Last spring, Alain Senderens, chef of the three-star Lucas Carton, shut down the restaurant after 28 years at the top of the Michelin ratings. „I didn’t believe in this luxurious and expensive system any more,“ said the 66-year-old Senderens. „Those bills at 400 euros, we don’t need them anymore.“ That’s about $480.

He opened a more informal restaurant — which he named Senderens, after himself — with meals that don’t exceed 110 euros and less fuss and frills.

But there was no escaping Michelin. Six months after his opening, the new edition is awarding Senderens’ sleek new establishment with its Asian flavors two stars — the fastest rise of any restaurant in the guidebook’s history. According to director Naret, it is „the first two-star with no tablecloth on the table.“

„I’m very happy and proud of my two stars,“ Senderens said. „But that won’t make me change my philosophy.“

The French edition of the Michelin Red Guide, the restaurant and hotel bible for tens of thousands of travelers, is bowing to some of these shifting trends. In this year’s edition, which goes on sale next week, 50 new one-star citations have been awarded to French restaurants — one of the biggest additions ever for the guide, according to Naret.

„There are some incredible young chefs going back to villages and opening restaurants,“ Naret said. „French gastronomy is definitely not dead.“

In this year’s France guide, 425 single stars were awarded, 17 double stars and 26 triple stars.

But many chefs say the cost of maintaining a restaurant to Michelin star specifications, with all the corresponding demands for big staffs providing overly attentive service for overly pricey plates, has become too high.

„The economic situation is far from being good,“ said Philippe Gaertner, the 50-year-old chef of Aux Armes de France in the Alsatian town of Ammerschwihr. In 2003, he decided to „turn down“ the Michelin star that had been next to the family restaurant’s name for 67 years. (Naret insists chefs don’t have the option of accepting or rejecting stars, a decision left up to the guide.)

„Every day you hear about a new plant shutting down,“ Gaertner said. „People live in fear, and restaurants are the last thing on their mind. Today, to eat a good meal with friends at a restaurant, it’ll cost you the same as going away to a sunny place.“

He simplified his menu and trimmed the average price of a meal from about $108 to $72, he said.

Rene Berges, chef of the Relais Sainte-Victoire in Provence, which held a Michelin star for a dozen years, quit chasing the Red Guide awards for another reason. „With the star comes a certain type of clientele,“ he said. „They expect you to have only small tables and no children.“

Chefs across the country were shaken three years ago when Bernard Loiseau, chef of the three-star La Cote d’Or in the Burgundy region, killed himself after restaurant critics reported rumors that he was about to lose one of the stars.

Many people in the French restaurant world blamed the rating system, but Naret rejected that. „The pressure doesn’t come from Michelin,“ he said. „It’s very difficult to be at the top all the time — that’s where the pressure comes from.“

Researcher Marie Valla contributed to this report.

Fréttaskot

Örn Garðarsson

-

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun1 dagur síðan

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun1 dagur síðanNotað Og Nýtt – Facebook hópur til að selja/kaupa notuð eða ný tæki

-

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel2 dagar síðan

Nýtt bakarí, veitingahús, fisk- og kjötbúð og hótel2 dagar síðanNýr kafli í miðborginni, Gamla Reykjavík tekin til starfa

-

Markaðurinn4 dagar síðan

Markaðurinn4 dagar síðanReyndur kokkur óskast í vaktstjórastarf á Snæfellsnesi

-

Keppni3 dagar síðan

Keppni3 dagar síðanNational Fish & Chip Awards: Íslenskur sigur við Mývatn vekur athygli

-

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun3 dagar síðan

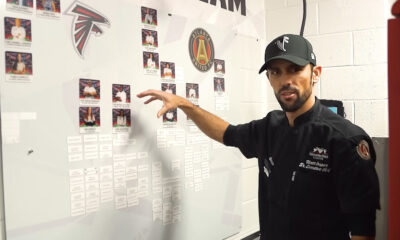

Viðtöl, örfréttir & frumraun3 dagar síðanEldhús í ofurkeyrslu: 1.000 starfsmenn umbreyta Mercedes-Benz Stadium á innan við 18 klukkustundum

-

Markaðurinn2 dagar síðan

Markaðurinn2 dagar síðanSegðu skilið við viðbrenndan grjónagraut í eitt skipti fyrir öll og prófaðu þessa aðferð

-

Markaðurinn6 dagar síðan

Markaðurinn6 dagar síðanAllt að 60% afsláttur af vinsælum vörum í takmarkaðan tíma

-

Markaðurinn3 dagar síðan

Markaðurinn3 dagar síðanHefur þú smakkað svart pepperoni?